Algal Blooms Might Pose a Threat to Respiratory Health

Haley Plaas is a doctoral student at UNC Chapel Hill’s Institute for Marine Sciences where she’s studying harmful algal blooms. But while we know what algal blooms do in the water, Plaas is studying something completely different: how they affect the air.

“We’ve been investigating the route of inhaling aerosols as a potential respiratory health issue,” she said in an interview with UNC Research. “Harmful algal blooms are actually naturally occurring, but humans are causing them to increase in their intensity and duration.”

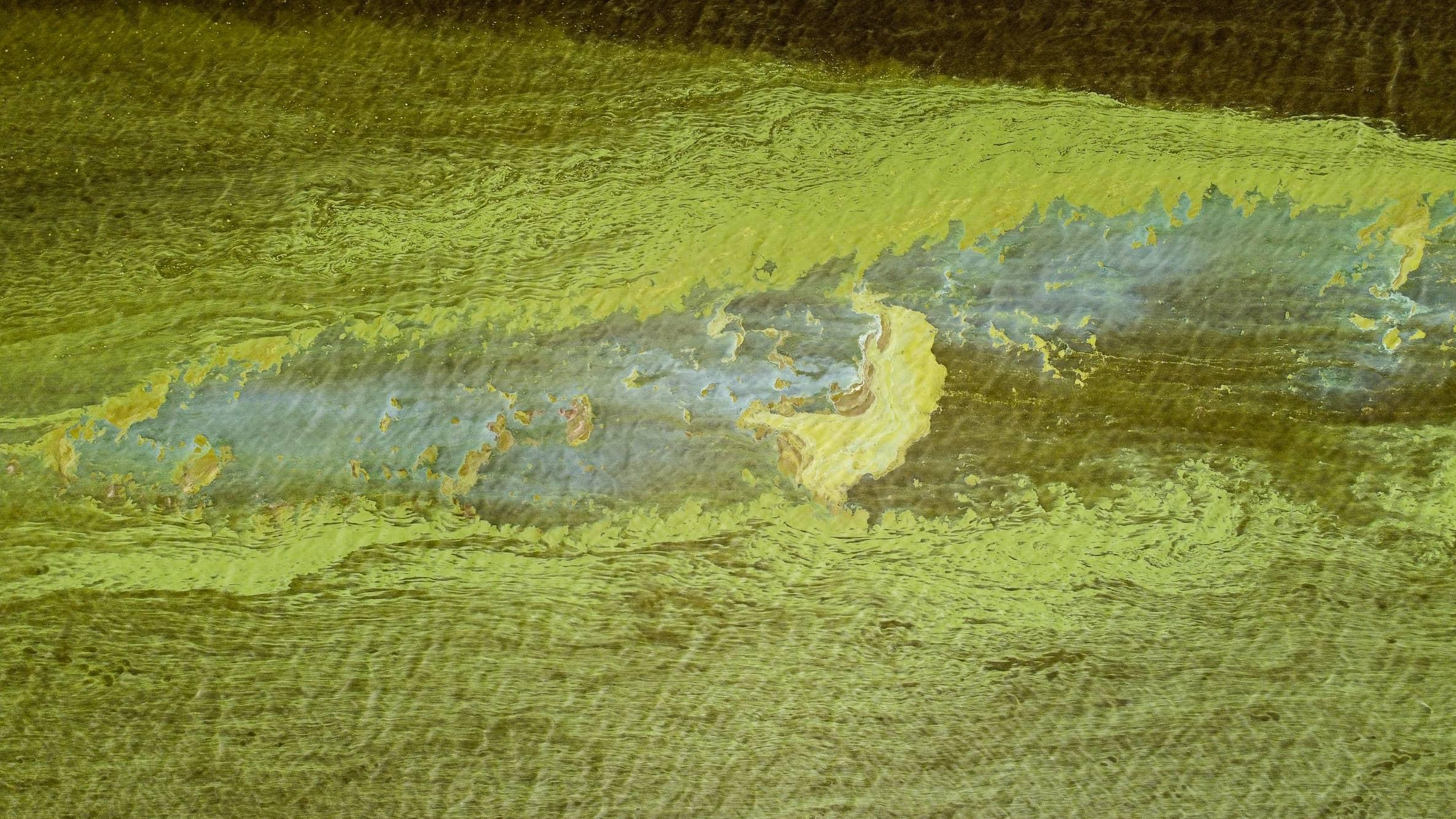

Algal blooms are caused by what’s commonly known as blue-green algae (although they're actually cyanobacteria rather than an algae). There’s almost always some amount of these cyanobacteria in the water, but a “bloom” occurs when the right conditions allow the bacteria to grow to really high levels. Blooms are common in the south, where temperatures are warm year-round, and they often form in slow moving, freshwater ecosystems that can range in size from backyard ponds to the Great Lakes.

You can often see when a bloom is happening because of visible “mats” of cyanobacteria in the water or on the shore, but toxic levels of bacteria can be present in the water even without any visible signs.

Algal blooms can create problems for other living things in an aquatic ecosystem. They physically block sunlight, keeping aquatic plants from thriving. Other organisms in the ecosystem can accumulate the toxins these bacteria produce, and those toxins can become more concentrated as they move up the food chain in a process known as bioaccumulation.

Blooms are known to produce neurotoxins and liver toxins, which can affect humans and animals that come into contact with the water. In 2019, several dogs in Wilmington, NC, died after swimming in a pond that had mats of cyanobacteria along the shore. Within hours of their exposure to the pond water, the three dogs had seizures and showed signs of liver failure.

Air bubbles are trapped below the water's surface by wind and waves, and as these air bubbles rise through the water column, they pick up particles and compounds from the water. When they reach the surface and burst, “microscopic aerosols” can carry cyanobacterial cells into the air where they have the potential to create a respiratory health issue for humans and animals. Sometimes these cells can travel as far as two miles away.

Plaas’s current work involves collecting aerosol and water samples from various points along the Chowan River in northeastern North Carolina with the help of a team of community scientists from the Chowan Edenton Environmental Group. There are currently no public health guidelines in place for aerosolized bloom toxins, and the results of Plaas’ work in the Paerl Lab at the Institute for Marine Sciences will help to quantify the amount of toxins emitted from blooms and determine if they create a public health risk. She’ll also be examining how other factors, like nutrients and salinity affect the growth of cyanobacteria.

“If we can figure out what types of nutrients are making these blooms thrive, then we can work backward from that and figure out how to prevent them from getting that concentration of nutrients,” she said in an interview with UNC Research.

Nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizer, untreated sewage and storm water runoff, and even air pollution are all human-driven inputs of nutrients to freshwater systems. Climate change and increased rainfall are amplifying these effects by keeping things warmer year-round and washing more nutrient-carrying runoff into waterways

“The reason I really love harmful algal blooms, which I know is weird to say, but I think harmful algal blooms are a great way to illustrate, the impact that people can have on the environment,” Plaas said in an interview with UNC Research.

“People equals nutrients,” said Hans Paerl, a professor of marine and environmental sciences at IMS, in an interview with UNC Research. “The more people you pack into a watershed, the more nutrients end up getting generated and discharged.”

The problem isn’t impossible to solve, but better management practices are needed to reduce nutrient inputs into waterways. Using less fertilizer and avoiding applying fertilizer right before rainfall are two key actions Paerl highlights. We can also try to capture some of these nutrients before they make it into waterways using wastewater treatment processes or riparian buffers around agricultural lands and urban areas.

“We know a lot about how to start controlling blooms but the will has to come to deal with it,” Paerl said in an interview with UNC Research. “Given that we are running out of freshwater resources in many places, there’s certainly more pressure to do something about controlling them.”

Hear more from Haley and Dr. Paerl in this video produced by UNC Research:

Toxic blue-green algae has long proven to be harmful to the environment, human and animal health. While many studies examine the effects of ingestion or skin contact, PhD student Haley Plaas looks at a different angle: aerosol.