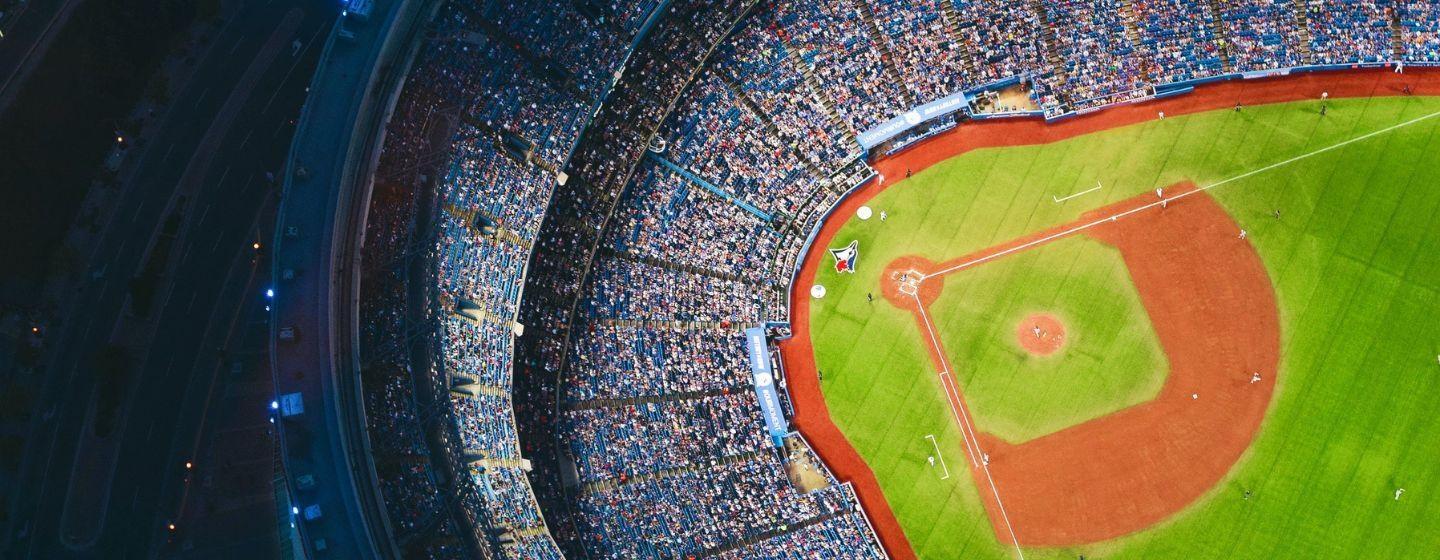

Home Runs and Climate Change

It’s probably safe to say baseball fans are into statistics. Earned run average (ERA), on-base percentage (OBP), slugging percentage—the list goes on. It doesn’t take long to confirm that as you walk through the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

And there’s no stat more revered than the record for most home runs in a single season. That honor goes to Barry Bonds, who launched 73 home runs in 2001. Before him, Mark McGwire held the record with 70 home runs in 1998. That mark broke Roger Maris’ long-standing record of 61 homers that was set in 1961.

But here’s where the debate begins. Maris’ record has an asterisk next to it because he played in ten more games than Babe Ruth, who hit 60 home runs in the 1927 season. Ruth was the first player to reach 60 home runs in a season.

In addition, Bonds and McGwire achieved their home-run records during baseball’s steroid years in the 1990s and early 2000s, so baseball purists question their achievements.

Most recently, the New York Yankees’ Aaron Judge is the latest player to top the 60-home run plateau, hitting 62 runs in 2022.

As a new baseball season begins, let’s add a new wrinkle to the debate.

A 2023 study out of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire suggests climate change may help home-run hitters clear the fences.

That’s right, climate change.

There are, of course, many factors that could account for those homes runs, including the construction of domed stadiums, better analytics about pitchers and even better training programs for players.

But the study finds that warmer temperatures have directly caused an increase in the number of home runs each season. Researchers looked at home-run data from 1962 through 2019. That’s 58 seasons and more than 110,000 games.

The conclusion: more than 500 home runs hit since 2010 were the result of a warmer climate.

“There’s a very clear mechanism at play in which warmer temperatures reduce the density of air,” said Justin Mankin, Dartmouth associate professor in the Department of Geography and a member of NOAA’s Drought Task Force. “Baseball is a game of ballistics, and a batted ball is going to fly farther on a warm day.”

To be clear, we’re not talking about many home runs. The data suggests about 50 additional home runs per year can be attributed to the warming of our climate. That’s not a large percentage when you consider 5,862 homers were belted during the 2023 regular season.

Mankin adds that “rising temperatures could account for 10% of home runs by 2100 if climate change continues at the current pace.”

It’s also reasonable to assume that more home runs will be hit during day games, when temperatures are higher. It will be interesting to see what happens as baseball shifts more day games to night games to avoid the heat.

In the meantime, “Play ball!”

Dartmouth’s study appeared in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.