How Planting Grasslands Fights Climate Change

“This is my favorite plant,” Tara Mei Smith exclaims to Justin Robinson while standing in a parking lot median at Chatham Mills in Pittsboro, North Carolina. “It’s like little stars,” she says, pointing out the silvery seed tufts of splitbeard bluestem grass that reflect the setting sun.

This plant isn’t something you’d normally find in a parking lot, but it turns out it’s uniquely adapted to thrive in this kind of exposed, sunny environment. The plants in these parking lot medians are cultivated by Chatham County Agricultural Extension Agent Debbie Roos as the Chatham Mills “Pollinator Paradise” Garden and include a variety of native species. But the ones Tara Mei and Justin are most excited about are the ones native to grassland ecosystems.

Tara Mei and Justin are part of the not-for-profit organization Extra Terrestrial Projects. One of their current missions is to help people realize the benefits of planting native grassland species (coneflowers, milkweed, asters) in commercial landscaping, roadside areas and residential yards where they’ll thrive. Doing so will help mitigate a major component of what’s causing our changing climate: excess atmospheric carbon.

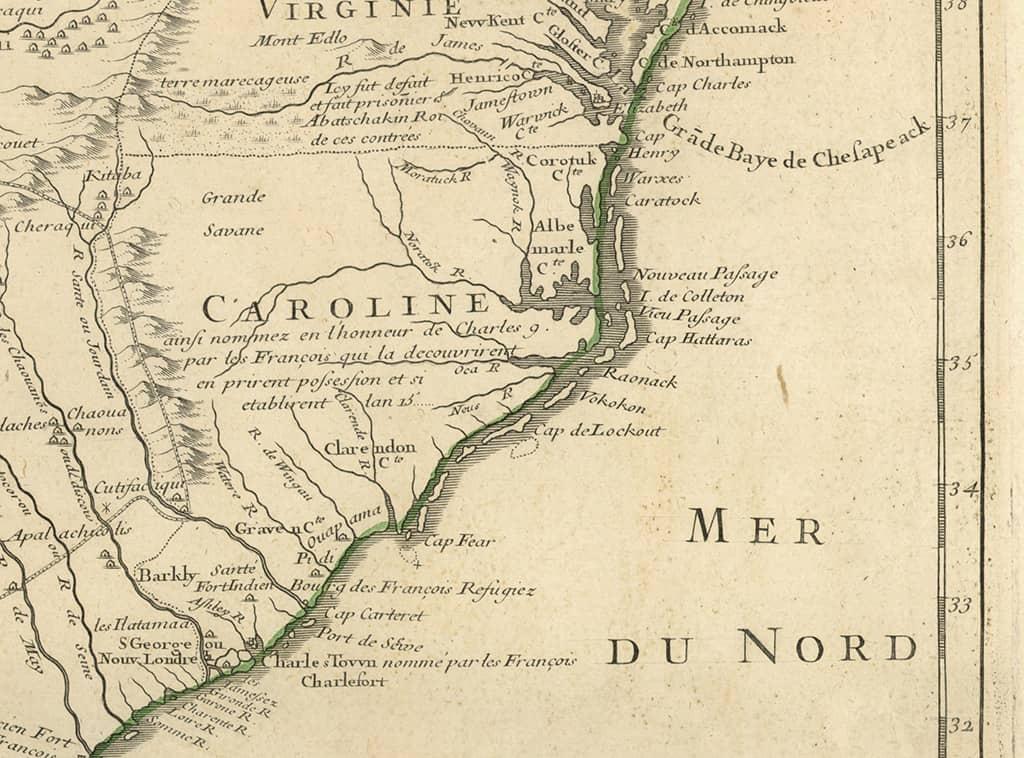

Grasslands (also called prairies or savannas) are a part of North Carolina’s ecological history. You might find that surprising given what the state looks like today.

“Grasslands are a fundamental part of our landscape,” says Tara Mei. “There are records that we can read dating back to the 1500s about grasslands. Anyone that came here that was a European would write about wading through the savanna.”

“And a lot of that had to do with how Indigenous people had been managing the land for thousands and thousands and thousands and thousands of years,” says Justin. He’s the sustainable landscapes manager for Extra Terrestrial Projects and an ethnobotanist (someone who studies how people of a particular culture or region make use of native plants). “That’s one of the things that made it so easy for Europeans to take over … it was already cleared. People weren’t clearing as many trees as we imagine. This was already a cultivated place.”

In North Carolina’s past, Indigenous people kept grasslands open and free of trees by setting them on fire. When a prairie ecosystem is exposed to fire, grassland species respond well by growing back quickly and tapping into deep roots for water and resources; trees and shrubs that aren’t adapted to fire are cleared out. Some prairie plant seed pods even require fire to open and disperse the seeds inside.

These days, fire is used less often to manage the land, and through the impact of development and encroaching forests, North Carolina’s Piedmont region has lost a lot of its ancient grasslands. One of the exceptions? Penny’s Bend Nature Preserve in Durham, which contains a remnant of ancient prairie managed by the North Carolina Botanical Garden (NCBG).

“There are over 50 different rare plant species here, two of which are federally endangered,” said Johnny Randall, NCBG’s Director of Conservation Programs, on a recent workday at Penny’s Bend, during which he and a small group cleared a new space to plant more grassland species.

The soil at Penny’s Bend is derived from an igneous rock called diabase, which creates unique conditions. Johnny described the soil as a “high shrink-swell clay” that’s like concrete in the summer and gummy when it’s wet in the winter.

Johnny explained, “Because of the soil type here, there’s a particular flora that has evolved on sites like this, and it’s part of the larger Piedmont Savanna or Piedmont Prairie plant community.”

Grassland plants are heliophytic, or sun loving. When they’re shaded out, they disappear.

“Especially here in the southeast and North Carolina, grasslands have this very, very, very strong connection with human beings,” Justin said. During a 2020 study surveying the locations of species and communities associated with the Piedmont Savanna ecosystem, Justin found them along roadsides, in power line easements and other places where human activities prevent tree canopies from closing in.

“In power line easements that have not been ‘herbicided’ to death, we find these plants that look like they belong in the Midwest,” he observed. “We find the big prairie grasses, we find the asters, we find the echinacea, the coneflowers. We find them in these places because they are the right kinds of conditions.”

Native plant species are uniquely adapted to thrive in the Piedmont.

“Plants that are from here are able to cope with all of the different dynamics that are going to happen. Remember, they have to be really, really good at that because plants cannot move!” Justin exclaimed. “Plants have to prepare for the extreme events.”

“Native plants have a relationship to this place for thousands of years. That includes the soil, that includes the rain, that includes the humidity, that includes the heat,” Tara Mei explains. “So they’re just going to be more climate resilient, and then they’re also going to interact better with all the pollinators, the birds and the insects, and be more abundant.”

Native plants’ adaptation to local conditions makes them a low-maintenance choice for landscaping, but this resilience might also help them survive our rapidly changing climate.

“There are a lot of climate models out there, and still it’s uncertain what’s going to happen as climate changes,” Johnny says. “Some of the models show that the Piedmont will become hotter and drier. Well, that’s okay for these Piedmont Savanna species, because that’s what they’re adapted to. They have seen so many different climates throughout their genetic memory. So we’re hoping that the Piedmont is a place where there’s a tremendous amount of resilience among the native plants here.”

Many grassland plants have deep root systems, some extending up to 10 feet below ground, and that allows them to tap into extra moisture and nutrients.

As deep-rooted grassland species grow, they actually change the soil around them, building up an ecosystem of microbes and releasing chemicals from their roots that improve the soil’s ability to store carbon.

“There are studies that show that the chemicals that come from grassland roots actually stay in the soil up to centuries, unlike leaf litter. So they’re working to sequester carbon for centuries,” Tara Mei explained.

And that’s their hidden superpower when it comes to fighting climate change.

Excess atmospheric carbon has long been identified as one of the main culprits when it comes to our changing climate. Carbon dioxide in our atmosphere acts like a warming blanket wrapped around the planet. We need this blanket to keep the planet warm enough for us to live on, but industrial production has increased levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to the point where the blanket is essentially getting too heavy.

Research published in 2017 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences demonstrated that nature-based solutions can provide up to 37% of the emission reductions needed by 2030 to keep global temperature increases under 2 degrees Celsius/35.6 degrees Fahrenheit.

“That’s incredible,” Tara Mei reflected. “If we just restore degraded landscapes … we can make a huge difference in the future of our planet.”

Rather than cutting emissions, natural climate solutions are often focused on pulling excess carbon out of the atmosphere and storing it underground, also known as creating a carbon sink. And guess what? Deep-rooted grassland species are really good at sequestering carbon.

“These savanna ecosystems have the potential to store a lot of carbon,” Johnny said.

Even when these ecosystems are burned by fire, most of the carbon remains stored below ground, unlike a forest where most of the carbon is stored above ground in the vegetation.

“90% of grasslands’ carbon sinks are below ground, which is really incredibly stable,” Tara Mei said.

Tara Mei and Justin hope to help municipalities, organizations, companies and even home gardeners realize that native grassland plants can be used in their landscaping and still have an impact on carbon sequestration. But this approach requires a shift away from the traditional garden plan.

“A lot of our historical gardens are based on a dominant English idea of a formal garden with a yard and very controlled plantings. And so that’s not necessarily made out of the plants that are native to this region and that would thrive the most in this region,” Tara Mei explains. “We’re in the Piedmont and North Carolina. It is humid, but it’s certainly not misty and wet, and it’s certainly a lot hotter [than England]. So that means that we should be thinking about planting in a different way.”

Tara Mei and Justin shared things to consider when planting native prairie species. “Our method that we use requires no water, no mulch, no fertilizers, no soil amendments. The plant is the soil amendment itself,” Justin explained.

Contrary to popular gardening practice, they don’t recommend watering these plants immediately after planting. Instead, plant on a day when rain has softened and moistened the soil.

“Overwatering can make the plant expect to have too much water,” Tara Mei instructed. “It’s sort of like when you put it in the ground, you’re getting the plant used to its new home. It’s going to adapt to its new home. And so you want to set it up for the conditions in which it’s going to be living for its whole life cycle.”

And mulching grassland plants is a major faux pas.

“A lot of times people in the Piedmont use too much mulch when they’re really planting plants that would thrive in a dry landscape that really doesn’t need a lot of mulch,” Tara Mei shared. Most grassland plant seeds also need to come in contact with bare ground in order to germinate, and mulch prevents that from happening.

Planting at the right time and the right place is also key. Grassland plants need sun so they won’t thrive in shady areas. And plants should be transplanted when they’re dormant, not when they’re growing and flowering. That’s when they’re putting their energy into reproducing.

“You don't want to send somebody who is pregnant on a long journey and have them move from house to house, you know, in the third trimester, right? [Plants] are at their most vulnerable time when they are flowering,” Justin shared.

Johnny suggests that homeowners consider planting grassland species, like tall indiangrass, little bluestem or a species of aster, even if they only have space for a small “pocket prairie” in their yard.

“I think that even ten feet square is better than having lawn grass there, because the plants that you would hopefully put in that site would be native, would be ones that are these remnants of the Piedmont Savanna or Piedmont Prairie,” he suggested. “They have the deep roots, and they support local biodiversity.”

Tara Mei mentioned that municipalities and government bodies are thinking about natural carbon sinks (ecosystems that absorb more carbon from the atmosphere than they release), and are just starting to discuss the value of grasslands. Previously, more energy has been focused on other ecosystems like forests.

“We think that grasslands are about a third of the global carbon sinks, which is really important,” Tara Mei emphasized. “A lot of people talk about the tyranny of trees. Not that trees are bad, but it’s just that when we think about carbon sinks and plants, a lot of times we think about trees and overlook grasslands.”

Tara Mei described the work of Extra Terrestrial Projects as “ecological time travel.” Their goal “is to get people to think about the past as it informs the future and create sustainable futures.”

“It’s really important that we also think about these amazing plants that are indigenous to the Piedmont, very abundant and very easy to plant,” Tara Mei urged. “Just think about all of our roadways and … all of our underutilized carbon sinks and backyards and empty lots that could be turned into grasslands and could sequester carbon and foster biodiversity, filter storm water ... that’s an incredible potential.”

“It’s an easy solution,” Justin emphasized. “We’re not trying to, you know, build the machines that live and spin around in the ocean. This is already here!”

Grasslands are a surprising part of the North Carolina Piedmont’s ecological history. Learn how planting native grassland species in our yards and other open areas mimics historical landscapes while improving the soil and fighting our changing climate.

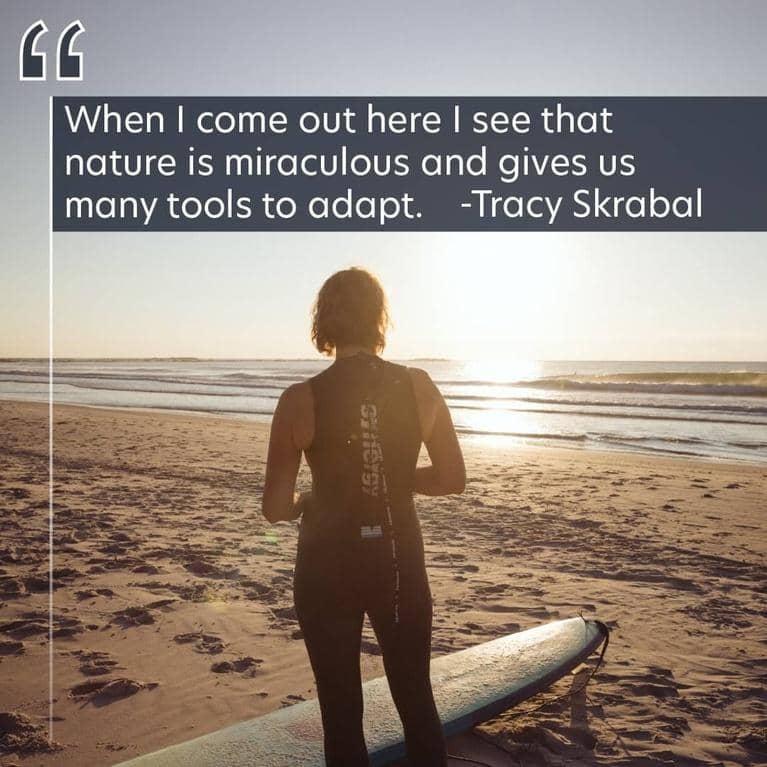

Sea-level rise and erosion directly impact North Carolina’s coastal communities, while extreme weather events bring the effects of climate change to communities across the state. Hear from North Carolinians who have responded to the challenges of climate change in new and innovative ways.

Farmers and researchers in Reidsville see the positive impacts of no-till agriculture.

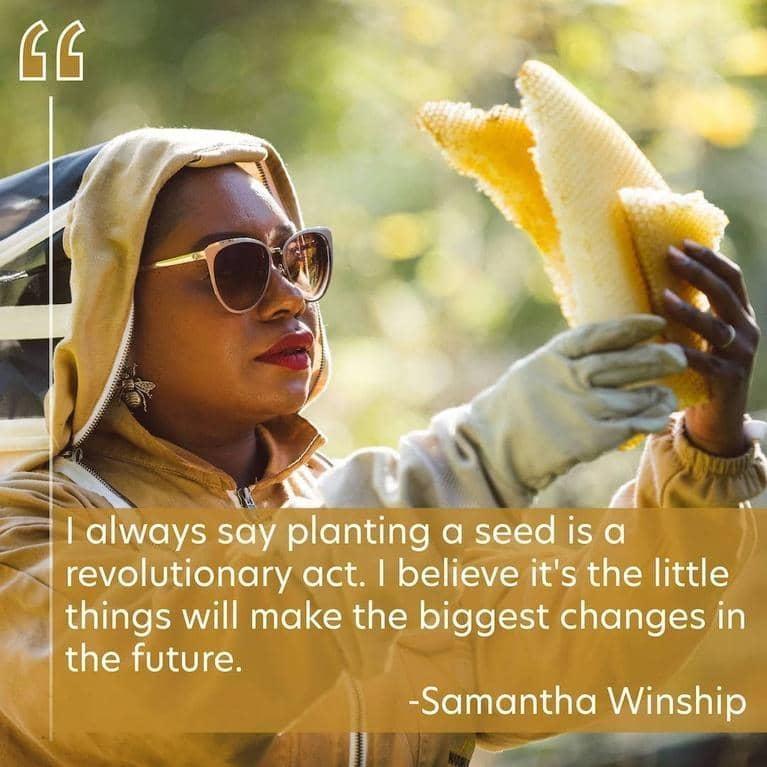

Farmers like Samantha Winship pay attention to shifting weather patterns. They know firsthand that the climate is changing.

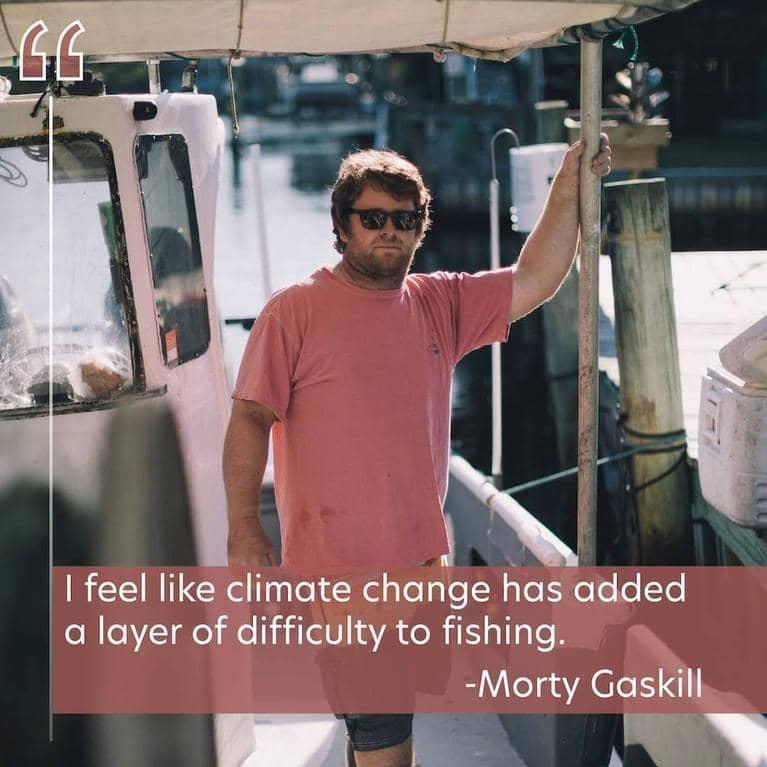

Warming waters present more change in diverse fisheries. Commercial fishers are adapting.

Coastal regions in the U.S. are some of the most densely populated areas in the country, and they are also the most vulnerable to sea level rise.

STREAM ANYTIME, ANYWHERE