The USS North Carolina Battles Sea Level Rise

“We’re on the river, so we see the river every day. And the condition of your environment then becomes something that you almost unconsciously track,” Terry DeMeo shared while standing on the boardwalk that surrounds the Battleship North Carolina memorial in Wilmington.

Terry is the development director at the battleship. After tracking increased frequency of flooding at the site, the battleship team has recently undertaken a massive project called Living with Water to adapt to environmental changes and build resilience through a variety of natural solutions.

The USS North Carolina (BB-55) was commissioned in 1941. It was the first of the United States’ fast battleships and was designed and built for World War II.

On July 11, 1942, the USS North Carolina was the first major ship to enter Pearl Harbor after the naval base was bombed the previous December. It saw action in every major event in the Pacific Theater from then until the signing of the treaty with Japan that marked the end of the war in 1945. The ship earned 15 battle stars and is the highest-decorated U.S. battleship of World War II.

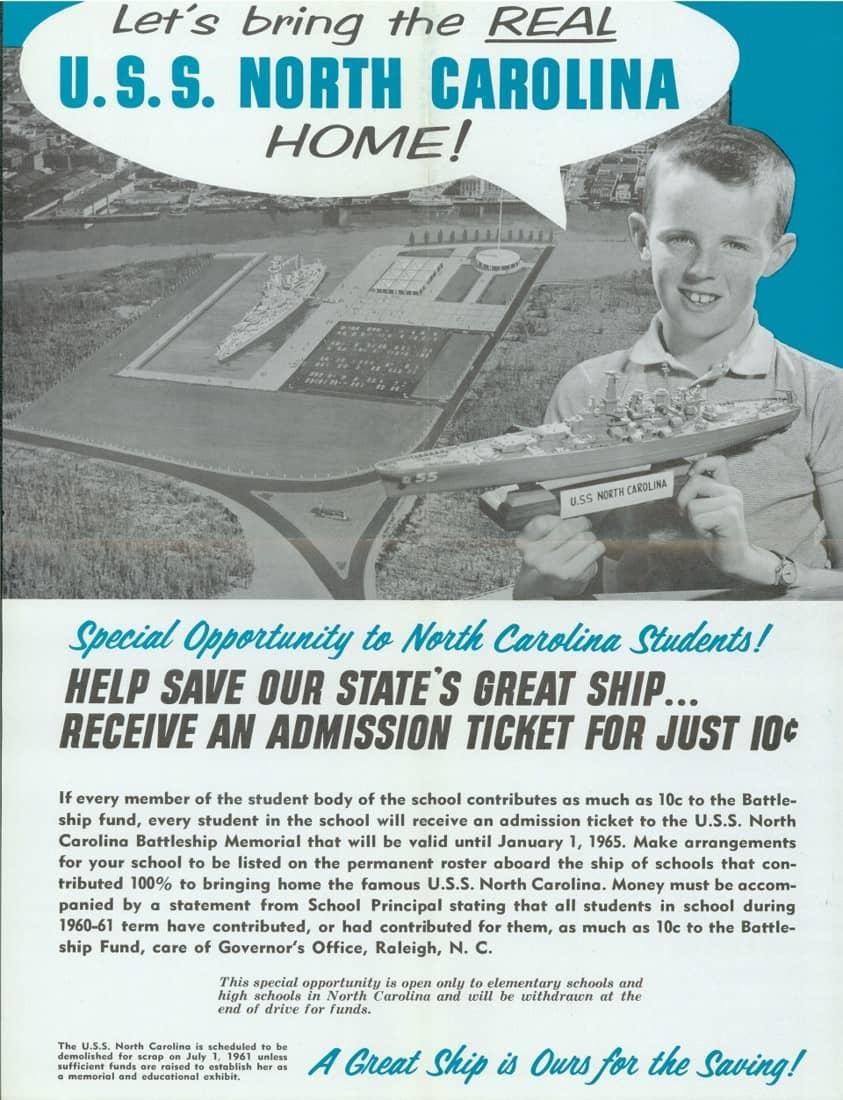

After the war, the ship served as a training vessel before being decommissioned in 1947. When the U.S. Navy was getting ready to send older ships to the scrapyard in the late 1950s, representatives in North Carolina were contacted to see if they wanted the ship. A statewide “Save Our Ship” campaign was launched to bring the battleship home to its name state. Part of the campaign was a collaboration with North Carolina’s schoolchildren.

“If schoolchildren donated their pennies, their nickels and dimes, and every child in your school donated, then all the children in the school received a free ticket to the Battleship North Carolina,” Terry explained. “The organizers were smart enough to know that those children would not be able to travel on their own, so they would bring their families. And that created the first wave of visitors to the Battleship North Carolina. It also created a passion for the ship and a love of the ship.”

In fact, not long after Terry started working at the battleship in 2019, a visitor showed up with his unredeemed free ticket to visit the ship.

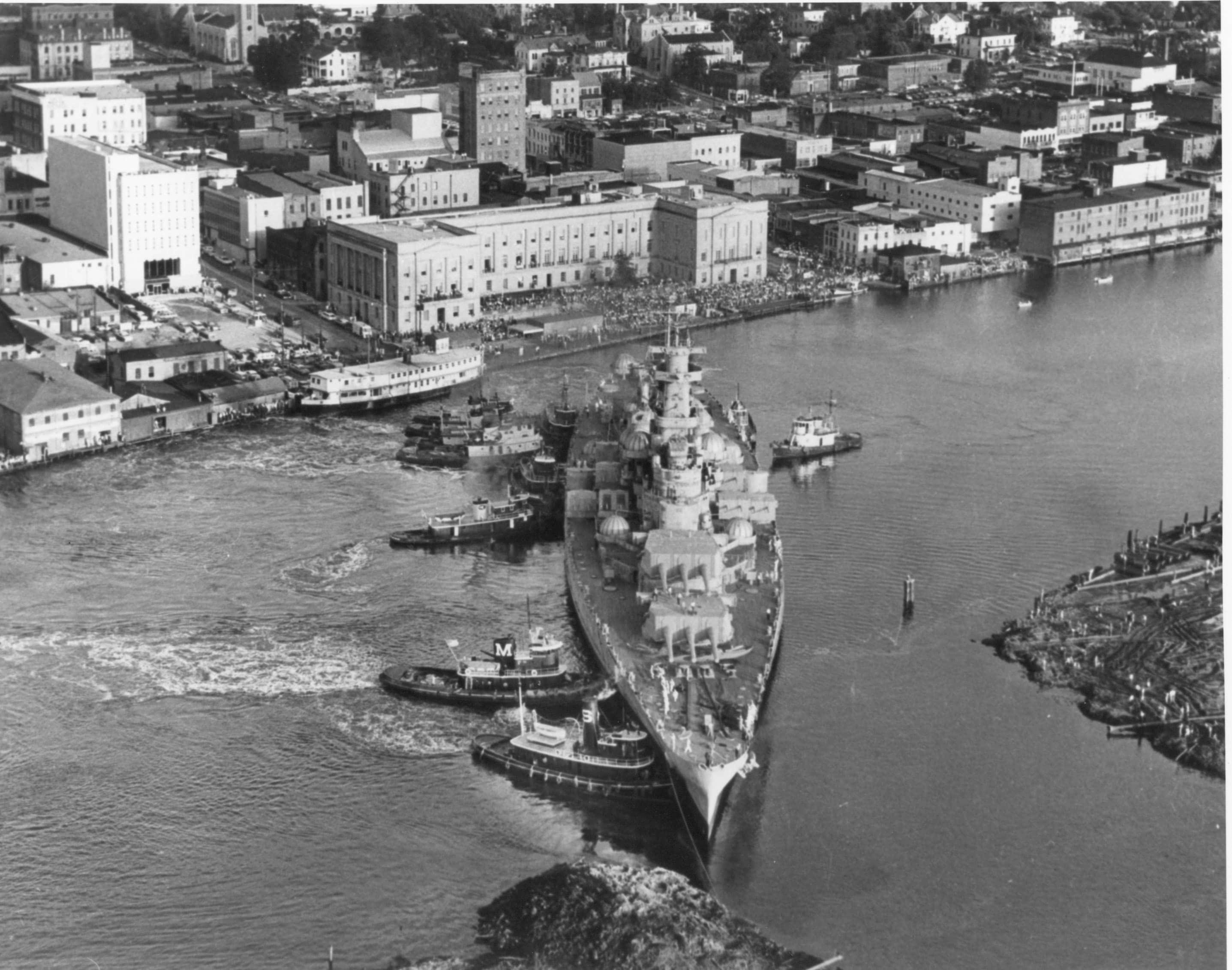

The battleship was moved to Wilmington in 1961 and now serves as a memorial to the 11,000+ North Carolinians who died in World War II. A visitor center, guided and self-guided tours and a boardwalk built around the ship offer visitors many ways to explore and engage with the ship and its surroundings.

The battleship sits, in Terry’s words, at “an interesting place where a lot is happening in terms of hydrology.”

The ship is located in the Lower Cape Fear River, adjacent to where the Northeast Cape Fear River merges with the Cape Fear River itself. It’s not far upstream of where the river flows into the Atlantic Ocean, so the site experiences both freshwater input from rainfall events upriver and tidal influences that bring two low and two high saltwater tides per day. From where the battleship is berthed on Eagles Island, you can look across the Cape Fear River at downtown Wilmington.

The berth was carved out of a marsh when the ship arrived in North Carolina. Because it’s surrounded by water and marshy wetlands, the battleship directly experiences the effects of sea level rise and more extreme storms brought on by climate change.

“In coastal areas like this, we have, honestly, a multitude of potential impacts from climate change,” said Dr. Devon Eulie, who is monitoring the project as leader of the Coastal and Estuarine Studies Lab at UNC Wilmington (UNCW). “One of the most obvious being increased flooding.”

Sea level rise is pushing salty floodwaters farther into freshwater ecosystems, which Dr. Eulie explained can impact the vegetation and other organisms that inhabit these coastal environments.

“It also makes it a challenge for the people who live here and all of the infrastructure that’s necessary to support them,” she explained, “whether it’s homes, the battleship site or businesses.”

In 2015, leadership at the battleship started to notice that access to the ship was being impacted more and more often by flooding on the road leading to the site and in the parking lot.

Terry set out to figure out just how much more often.

A National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) tidal gauge, established in 1908 on the nearby Cape Fear Memorial Bridge, gave her a lot of information. The bridge is just a half mile downstream from the battleship’s berth, and comparison of the data at the site and at the bridge showed that their conditions mirrored each other. The data from the tidal gauge, which is one of the longest-running tidal records on the East Coast, documents flooding levels and frequency for the battleship site over the course of the last 100+ years.

“I have an academic background, and so I decided to do a trend analysis to find out how much the flooding may be changing over time,” Terry explained.

After crunching the numbers in a historic trend analysis from the 1940s through 2020, Terry made a big discovery.

“The results showed an over 7,000% increase in tidal flooding since the battleship arrived in Wilmington in 1961,” Terry shared.

That meant the number of days each year the site was experiencing flooding had increased dramatically. Terry’s analysis showed an increase from double-digit counts of days with tidal flooding from the 1940s through the 1960s to triple digits today.

“In the last full decade, the tidal flooding had increased 770%,” she explained. “Clearly, the tides were getting worse, and the frequency was getting greater as well.”

A unique aspect of the battleship site that makes increased flooding particularly impactful is how its operations are funded. The battleship is an enterprise of the state of North Carolina, which means it relies on ticket sales and visitor purchases, in addition to donations, to keep its doors open.

A flooded roadway and flooded parking lot meant visitors were unable to access the ship.

“Because we’re required by law to operate under revenues generated through ticket sales and gift shop sales, if visitors can’t get to our site or are not comfortable parking once they get here and they turn around and leave, then our business model is threatened, and ultimately, we will not be able to be sustainable financially,” Terry explained. “There was a real economic impact to our operations and the survival of the ship.”

As days with severe flooding crept into the triple digits, the battleship leadership started to realize something needed to be done.

“When you are in a situation like that where … the existence of our staff, our mission, even the ship itself are threatened, you’re willing to take risks to be able to preserve the mission, preserve the historic ship, preserve the marsh, all those things,” explained Dr. Jay Martin, who started as executive director of the Battleship North Carolina in spring 2024. “We’re willing to take more risks.”

The Living with Water project was born in 2018 after an exploration of options to reduce flooding at the battleship.

“The leadership really decided to go an innovative way with Living with Water rather than doing standard bulkhead and wall building to try to keep the water out,” Terry shared. “We decided to do nature-based infrastructure: the installation of softer systems to be able to capture the tides and find a way for it to sit on our site without impacting us negatively and then to be able to drain back to the river at low tides.”

The battleship partnered with design firm Moffatt and Nichol to determine what infrastructure was needed to build flood resilience at the site. Funding support came from the North Carolina Land and Water Fund, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, NOAA, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the USS North Carolina Battleship Commission and individual donors.

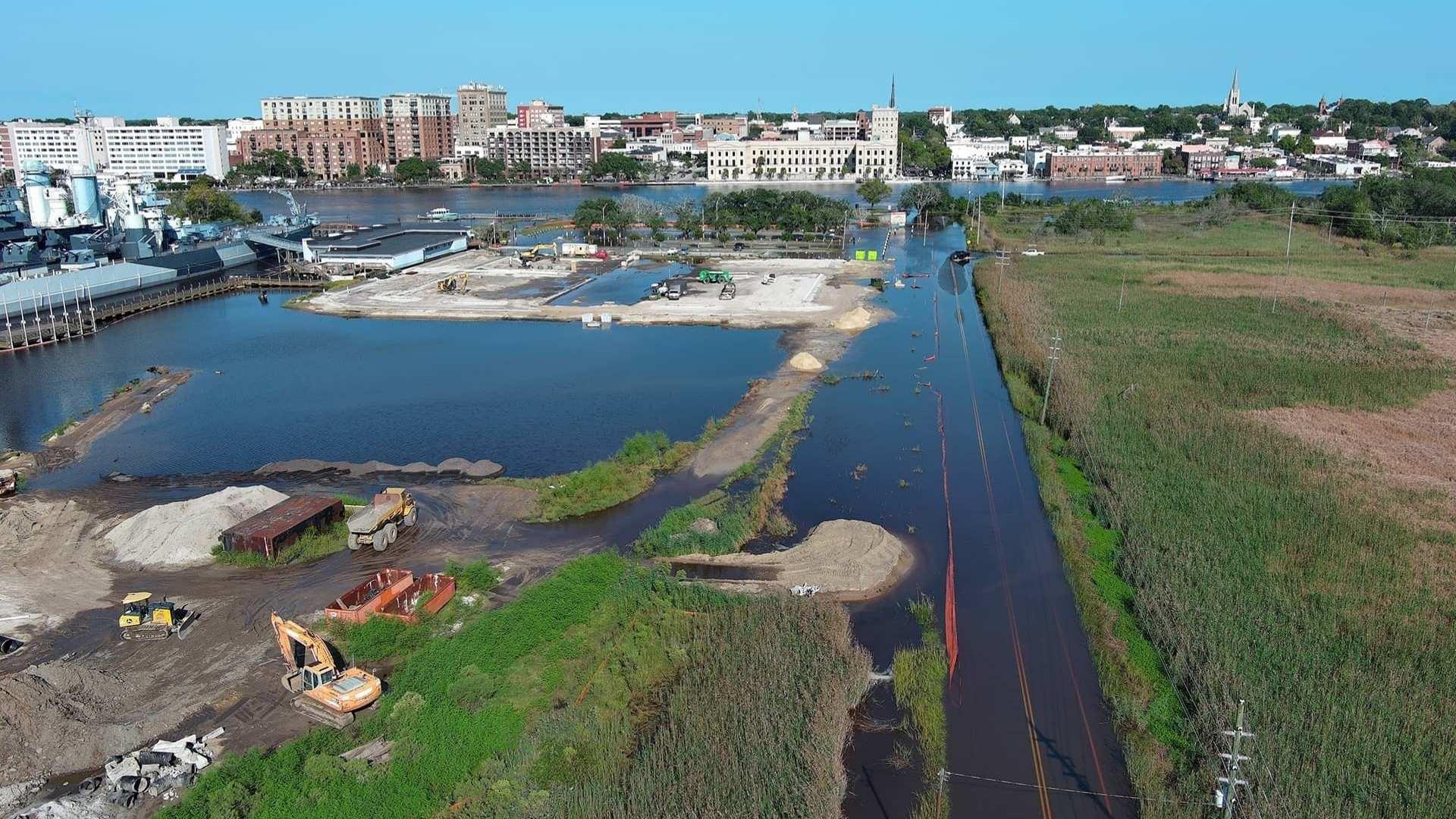

The project includes the restoration of more than 800 feet of hardened shoreline to a living shoreline, the return of a former parking area that flooded frequently to a tidal creek and wetland, elevation of the remaining parking area and the addition of bioswales (lower areas planted with vegetation) to collect and process rainwater.

The restored tidal creek and wetland area are particularly striking when you view older aerial images of the flooded parking lot side-by-side with where the creek and wetland are now. The most heavily flooded areas of the former parking lot directly overlap with the now-restored wetland. Dr. Eulie says by restoring natural infrastructure, the Living with Water project gives floodwaters somewhere to go.

“All of that happens synergistically in a natural system, and in a lot of these more built environments, like coastal areas around Wilmington where we have a lot of construction and things like that, we’ve taken away that ability for floodwater to be managed naturally,” she explains. “By putting in something like the tidal creek, the bioswale, the living shoreline, it provides an opportunity for that water to go somewhere that provides that more natural synergy with the landscape than what you would otherwise see.”

And it hasn’t taken wildlife long to move into the restored marsh.

“Almost as soon as the wetland was in place, the birds started to colonize it to, of course, be able to fish on the fish nursery habitat. But also, it’s perfect habitat for wading birds and such,” Terry shared.

To Dr. Eulie, the scale of the project and the variety of strategies are unique and promising.

“The fact that this is several hectares, several acres of property, that they are proactively creating this resilience and flood mitigation project on is almost unheard of,” she said.

“This is one of the first and largest projects to incorporate all of these different components in one site. And that kind of holistic approach is what we need going forward,” she explains. “That’s the only way to tackle these kind of big picture problems: from a holistic view.”

While it’s too soon to say anything definitive about the impacts of the project at this point (construction wraps up in 2025), data has already been collected, which, according to Dr. Eulie, is unusual for a restoration project.

“Usually I get a call that, ‘Hey, we’ve already done this. I think it might be doing something. Can you come out and tell us if it’s working?’” Dr. Eulie shared. “This is the kind of thing that people in my field dream of being called in and asked to join from the ground up.”

Dr. Eulie met Terry in the early stages of the projectat meetings for the Eagles Island Coalition, a group of public and private entities working to further conservation goals for the island. When Dr. Eulie learned more about what the project involved, she was excited to be part of the team monitoring its impacts.

“This project is honestly one-of-a-kind in the state,” she states. “It’s almost unheard of. When she called me and said that they wanted to … rip out part of their parking lot and restore a tidal wetland, put in several hundred feet of living shoreline and basically redo an entire section of their property, several acres, into this resilience project, that’s not a call I usually get.”

Several labs from UNCW are monitoring the site with Dr. Eulie as the lead investigator. Other UNCW researchers include Amy Long, a restoration ecology specialist, and Dr. Martin Posey and Troy Alphin, who study benthic ecology, the study of organisms that live on or near the ocean floor.

The team from UNCW is currently monitoring a series of stations for everything from water quality to habitat utilization via frequent site visits and tools that collect data continuously.

Dr. Eulie shared that in addition to having the opportunity to collect baseline data, the team was also able to continue collecting data during construction of the project.

“That is actually a piece of the science that is a big unknown: ‘What is the impact of the process of constructing resilience projects ... in these large scales?’” she explained.

And all of that serves as an additional focus of the Living with Water project: education. Students at UNCW are getting access and exposure to an ongoing research project at a coastal resilience project.

“It provides this incredible local opportunity for students to be able to come out here, be involved in an applied community project and also collect data and learn skills that they can apply to a future professional career,” Dr. Eulie shared. “Even just outreach opportunities for different groups to come here and do a local field trip and see science in action is incredible.”

Work is being done to create what has been dubbed a “living laboratory” to allow for learning and research outside of UNCW’s work. And Dr. Martin says that the restoration work has sparked an interest in more environmentally related educational programming from the battleship.

“We’re pivoting to tell more of that story because it’s so easy from the platform, which is the ship, and the adjacent Living with Water project to show exactly what the impacts are of global warming, of sea level rise,” he expanded. “All of those things can be done in this one place. So it actually has led to an opportunity for us to relook at what we do and be able to interpret our coastal heritage in an entirely different way, taking into account our very fragile marine environment.”

Beyond academic education, Terry and Dr. Martin are aware that the battleship’s approach with Living with Water could serveas a model for other coastal sites and the climate change impact they’re experiencing.

“One of the things that we realized early on at the battleship is that we’re not unique in this impact and effects—that there are many communities along the coast who are similarly being impacted by rising seas and tidal flooding,” Terry said. “We realized that we had an opportunity to install some unique aspects to manage our tidal flooding and to document how well they are working and to share that information with others. And in that way, we were becoming kind of a center of education around dealing with rising seas.”

“The environmental research bank that has been created by this project will help scholars for decades in the future be able to look at these kinds of environments where you have a natural environment that was lightly impacted over time and then, right next to it, an environment that was heavily impacted by humans over time,” Dr. Martin expands. “Ultimately, this project demonstrates why unrestrained development of and filling of our marshlands is absolutely unsustainable.”

Tidal flooding skyrocketed at Battleship North Carolina. Natural systems may be the key to survival.

Learn how NC communities have increased their resilience to climate change by returning waterways to a natural state. Stories include how the Battleship North Carolina modified its marshy surroundings to adapt to rising sea levels, how Conserving Carolina is working to restore floodplains in western NC and how the Coharie Indian Tribe is reconnecting with the river they’ve lived on for centuries.

The Coharie Tribe has lived on the Great Coharie River for centuries. Can a new initiative help reconnect the next generation to the water and their culture?

Farmland is being lost to development at an alarming rate. What if solar energy could provide farms with steady revenue and share the field with valuable crops?

PBS NC producer Michelle Lotker and clean energy expert Steve Kalland of NC State discuss solar energy production in North Carolina and look toward the future.

A farm in Biscoe, NC, generates renewable energy while its sheep keep the grass trimmed without gas-powered machinery, a win-win for climate change resilience.